After Steve McQueen’s Widows kick-started the London Film Festival in style, here’s our reviews of two of the best films we have watched from this year’s programme so far. Two very different works dealing with personal and financial struggles: a socio-political essay offering proof about the ravages caused by modern capitalism and its neoliberal doctrines (The Plan) and a faithful literary adaptation of one of Richard Ford’s short stories about family hardship (Wildlife).

THE PLAN THAT CAME FROM THE BOTTOM UP (Steve Sprung)

There’s a chilling archive scene rather early in ‘The Plan’ that shows Margaret Thatcher thanking general Pinochet “for bringing democracy to Chile.” It works as an early example of fake news or political cynicism of the first order, as everybody knows the Chilean dictator led a coup that ended with the democratically elected socialist government of Salvador Allende. Looking back, Chile seems to have been used like a lab rat in an economic experiment to implement, by all means necessary, the damaging free market neoliberal doctrines that, decades after having been universally adopted , are responsible for the enormous wealth divide, environmental decay and socio-political turmoil the world is experiencing Today.

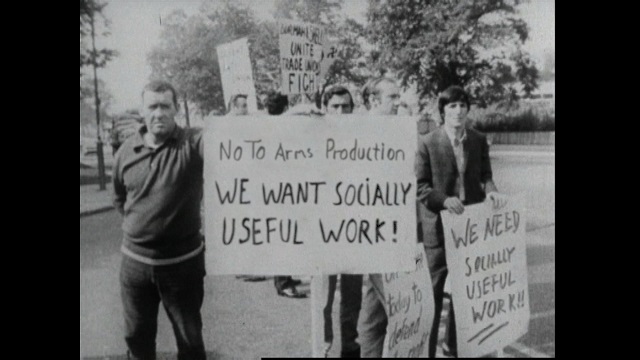

The Plan That Came From The Bottom Up is a lovingly crafted and rigorously researched essay that deals with the ravages that those capitalist hegemonic ideologies have caused in the world, from the perspective of a time and place in history that could have proven instrumental for positive social transformation. This documentary tells the story of a group of highly-skilled engineers and workers of a British company producing military items, Lucas Aerospace UK, whom in the 1970’s facing a time of factories restructuring and massive redundancies, as well as expressing their rejection for their industry’s involvement in the pmaking of weapons Chile’s coup was won with, organised themselves in order to demilitarise the company’s functions and beginning the design of socially useful and environmentally sustainable products. Among their proposals there were such innovative items as wind turbines, a hybrid car, heat pump and an energy efficient house.

These events marked an early moment in history where people tried to take control of their means of livelihood for the benefit of the many, just to encounter widespread rejection amongst their management, being also shut down and condemned into oblivion by Government and political institutions.

One of the films in competition for The Grierson Award, ‘The Plan’ is loosely structured in episodes, documenting the long gestation and even longer and frustrating negotiations to put this project into place through testimonial interviews with the engineers that shaped it up. It’s very well backed by archive material showing both their time and the many current catastrophic consequences caused by our society’s ignoring socially-minded initiatives like this, favouring the neoliberal agenda.

Told in a melancholic voice that underlines what could have been but got lost in the mist of history, the film’s also finds time to show its director’s cinephilia, using many clips from well-known classics (from Orson Wells to John Wayne) to illustrate its relevant points.

Steve Sprung has put together a timely and thought-provoking call to arms, proving that a better world is, and has always been, possible. But it would take collective debate, political struggle and communal spirit for our society to rise to the challenge and achieve it. ★★★★

WILDLIFE (Paul Dano)

After years of a successful acting career that has seen him taking part in such remarkable films as There Will Be Blood (2007), Love and Mercy (2014) or Little Miss Sunshine (2006), Paul Dano takes the director’s seat with an incredibly assured debut feature, adapting Richard Ford’s short story Wildlife.

Helped by his partner, Zoe Kazan, on writing duties, first thing that impresses in Wildlife is how faithful it is to the literary spirit of the writer. Ford’s work is renowned for its meticulous emotional observation of suburban families enduring all sorts of hardship in troubled times. A striking cinematography capturing the beauty of classic Americana and an elegantly austere mise-en-scène help delivering the intimate poignancy of this accomplished family drama whose main appeal is its three leading performances.

Wildlife tells the story of a young couple with a teenage kid whose attempts to find their place in the small Montana town where they have recently moved to are abruptly interrupted when the husband, a Jake Gyllenhaal at his most earnest and subdued, gets fired from his recent job at a golf club for being too personable with the clients. He begins a depressive and introspective search for purpose that will end with him joining a gang of wildfire extinguishers for a badly paid and dangerous task that will force him to leave his family behind for moths.

Carey Mulligan has never been better as the young wife who, bitter and disappointed of her domestic role, progressive takes control of her life, first by finding a job and then, feeling abandoned, by trying to seduce the town’s wealthy car dealer hoping to get a more settled future. In the middle of their crumbling marriage is their kid, an also excellent Ed Oxenbould, whose apprenticeship in the local photography store will be used as one of the film’s more powerful metaphors about the way we frame our lives. ★★★★

Altogether they shape up a slow burning, but very rewarding drama that will establish Dano as a filmmaker to follow.